Al-Faraheedi

Copyright © 2011-2018 Academia-srt Network, All Rights Reserved

Arabic Calligraphy

THE SIX ARABIC CALLIGRAPHIC STYLES

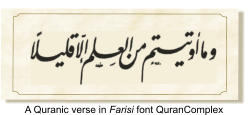

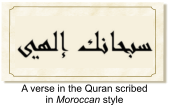

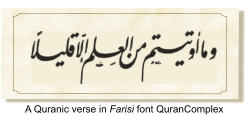

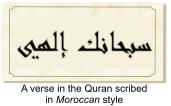

1. The Koufi Style: The Koufi font originated in the second decade of the Islamic era in the city of Koufa which was considered a political and artistic center in the Islamic empire. This form was a direct descendant of the Hijazi Meccan script and maintained the straight lines and right angles characterizing the original basic form. In this excellent style, the letters have a uniform pattern distinguished with its angular and square letters. The straight-lined text is elongated horizontally and vertically along the lines. It was only later afterwards that the "flowered" version of the koufi script appeared. In the newly developed form, letters were adorned and decorated with fan-like and blossoming patterns. This style was widespread in Egypt during the Fatimid and Ayyubid Caliphate era, and was a favorite script to the Siljiqi dynasty residing in the Anatolian heights during the Islamic rule. Prominent calligraphers of the Koufi style include Khalid bin Abi Al-Hayyag who lived in the first Hijri century. The Moroccan style, also known as the Andalusian font, evolved directly from the excellent Koufi script. Its geometric form qualified it for use in inscriptions and carvings on monumental and civil constructions which often displayed proverbs and passages from the Quran. 2. The Thuluth Style This script is known to be from the most attractive and elegant forms of Arabic calligraphy, as well as the most difficult to master. Its name originated from the width of the tip of the pen utilized to scribe with. This elegant style formulated in the 2nd Hjri century during the Umayyad Caliphate but did not develop fully until the late 9th century. In the Thuluth school, the alphabetical characters are scribed with curved lines ruled by complex proportions. This font was rarely used to scribe the Quran but selected in cases to scribe only the titles of chapters or to highlight certain verses. Variant forms and pens branched out from this style, most common known are the two fonts Naskh and Riq’a. When tutored in calligraphy, students would be taught the Thuluth and Naskh writing concurrently. The scripts were practiced together and usually the same masters taught both scripts. 3. The Naskh Style The forms of this style were derived from the Thuluth script as a modification with less rules regulating it. Naskh is a simple script easy to read and write which appealed to the public. It was called the Naskh (copyist) describing its function as it was a simple script used to copy manuscripts and elegant books. It first appeared in the Hijaz region in the 5th Hijri century when the need of it arose upon the increase of publications and literary work. The simple rules governing Naskh variants aided the writer who needed a swift pen to replicate literature. Soon the Quran was scribed around the 10th century of the Islamic era in this artistic font and illuminated versions were printed as it served to be both elegant and lucid. Renowned calligraphers include Ibn Muqlah whom founded the script and Ibn Al-Bawaab whom established its final geometric proportions. Another contributing calligrapher was Yaqout Al-Mustasimi from Baghdad whom appeared in the 7th Hijri century and whom regularized the sex pens of calligraphy. Naskh today is considered the dominate style in modern times preferred for Arabic print. The calligraphers whom established its mathematical principles include Qutbah Al-Muharrir whom lived during the Umayyad Caliphate and was known for converting the Koufi style to Thuluth, in addition to Ibn Muqlah 3rd Hijri century and Ibn Al-Bawaab whom appeared by the end of 4th Hijri century. The city of Damascus was known for contributing significant artwork in the Naskh style. In tradition, calligraphic artwork usually carried the signature of the calligrapher in order to identify his work. It was by the end of the 7th Hijri century that the different calligraphic pen styles spread rapidly appearing individually in other cultural centers of the expanding Islamic empire including the North African regions where the different forms of handwriting developed. 4. The Riqaa Style This pen style evolved from both the Naskh and Thuluth designs around 886 AH. Its name is derived from the riqaa sheet or leather spread used to scribe on. Riq’a is a simple script with geometric rules similar to those of Thuluth but with smaller characters displaying more curves and short horizontal stems. This font is the most practiced for handwriting and ranks after Naskh. Most contemporary scholars and students used a combined version of both pens. This distinct style emerged in the Ottoman era and only later afterwards adopted and appropriated by Arab artists. Today, children are taught Naskh then introduced to Riqaa. A leading calligrapher in the Riqaa font was Mumtaz bek, an apprentice to the Ottoman Sultan Abdul-Majeed Khan (1280 AH). 5. The Diwani Style. This was the official script of state and administration as can be inferred from its name and was indeed the style used in official writing. It was named the “royal script” as it was used mainly in the imperial palace and museums, and used to write most royal decrees. The word “diwan” in Arabic means “government’s offices”. Records of correspondences were scribed in Diwani as it was the favorite for chancellery, in addition to many other manuscripts kept in the caliphate library. The Diwani writing is highly structured spangled with decorative marks and characterized by its adorned and decorated tails. This style flourished during the Ottoman Caliphate and was practiced over a period of nearly five hundred years and delivered to the following generations whom produced illuminated inscriptions and artwork. The Diwani script was founded by the well known calligrapher Shaykh Hamad-Allah Al-Amasa in 926 AH. 6. The Farisi Style This style was also known as Ta’liq or Nas-ta’liq which combined both the Naskh and Ta’liq geometric drawing rules in its application. The beautiful Farisi or Persian script is known with its brisk letters all drawn in one direction. While drawn with lenient and cursive characters, the style is easier to master and was a favorite in ornamental objects. The Farisi style came in use since the early 9th Hijri century (16th century CE) and flourished in the eastern Islamic regions of Persia and India. 7. The Moroccan Style This font is derived directly from the Koufi style and regulated with similar geometrical principles, uniformly it developed its distinct form. It was initially named the Qirawani font attributed to the Qirawan the capital of the Moroccan province but later known as the Morrocan style. Many copies of the Quran were scribed in this font in the northern provinces of Africa as well as Andalusia. This script is characterized with rounded large letters. To date, the Quran is scribed consistently in north African countries with this unique font.References

• Al-Kurdi, M. T. (1939) The History of Arabic Calligraphy and Arts, Egypt, The Hilal Book Publishers (Arabic book). • Al-Oufi, M. S. (2002) The Development of the Arabic Quranic Script, Al-Medina, KSA, The King Fahd Quran Complex (Arabic reference).

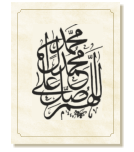

The Basmalah in traditional Koufi-

calligrapher Uthman Hamid, Kuwait

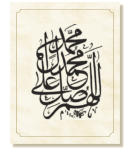

A prayer in Thuluth style

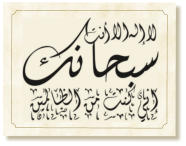

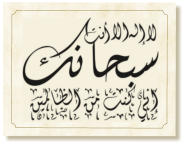

A prayer in Naskh style

Allah in simple Riqaa

A prayer in traditional Diwani Script

Al-Faraheedi

Copyright © 2011-2018 Academia-srt Network, All Rights Reserved

Arabic Calligraphy

THE SIX ARABIC CALLIGRAPHIC

STYLES

1. The Koufi Style: The Koufi font originated in the second decade of the Islamic era in the city of Koufa which was considered a political and artistic center in the Islamic empire. This form was a direct descendant of the Hijazi Meccan script and maintained the straight lines and right angles characterizing the original basic form. In this excellent style, the letters have a uniform pattern distinguished with its angular and square letters. The straight-lined text is elongated horizontally and vertically along the lines. It was only later afterwards that the "flowered" version of the koufi script appeared. In the newly developed form, letters were adorned and decorated with fan-like and blossoming patterns. This style was widespread in Egypt during the Fatimid and Ayyubid Caliphate era, and was a favorite script to the Siljiqi dynasty residing in the Anatolian heights during the Islamic rule. Prominent calligraphers of the Koufi style include Khalid bin Abi Al-Hayyag who lived in the first Hijri century. The Moroccan style, also known as the Andalusian font, evolved directly from the excellent Koufi script. Its geometric form qualified it for use in inscriptions and carvings on monumental and civil constructions which often displayed proverbs and passages from the Quran. 2. The Thuluth Style This script is known to be from the most attractive and elegant forms of Arabic calligraphy, as well as the most difficult to master. Its name originated from the width of the tip of the pen utilized to scribe with. This elegant style formulated in the 2nd Hjri century during the Umayyad Caliphate but did not develop fully until the late 9th century. In the Thuluth school, the alphabetical characters are scribed with curved lines ruled by complex proportions. This font was rarely used to scribe the Quran but selected in cases to scribe only the titles of chapters or to highlight certain verses. Variant forms and pens branched out from this style, most common known are the two fonts Naskh and Riq’a. When tutored in calligraphy, students would be taught the Thuluth and Naskh writing concurrently. The scripts were practiced together and usually the same masters taught both scripts. 3. The Naskh Style The forms of this style were derived from the Thuluth script as a modification with less rules regulating it. Naskh is a simple script easy to read and write which appealed to the public. It was called the Naskh (copyist) describing its function as it was a simple script used to copy manuscripts and elegant books. It first appeared in the Hijaz region in the 5th Hijri century when the need of it arose upon the increase of publications and literary work. The simple rules governing Naskh variants aided the writer who needed a swift pen to replicate literature. Soon the Quran was scribed around the 10th century of the Islamic era in this artistic font and illuminated versions were printed as it served to be both elegant and lucid. Renowned calligraphers include Ibn Muqlah whom founded the script and Ibn Al-Bawaab whom established its final geometric proportions. Another contributing calligrapher was Yaqout Al-Mustasimi from Baghdad whom appeared in the 7th Hijri century and whom regularized the sex pens of calligraphy. Naskh today is considered the dominate style in modern times preferred for Arabic print. The calligraphers whom established its mathematical principles include Qutbah Al-Muharrir whom lived during the Umayyad Caliphate and was known for converting the Koufi style to Thuluth, in addition to Ibn Muqlah 3rd Hijri century and Ibn Al-Bawaab whom appeared by the end of 4th Hijri century. The city of Damascus was known for contributing significant artwork in the Naskh style. In tradition, calligraphic artwork usually carried the signature of the calligrapher in order to identify his work. It was by the end of the 7th Hijri century that the different calligraphic pen styles spread rapidly appearing individually in other cultural centers of the expanding Islamic empire including the North African regions where the different forms of handwriting developed. 4. The Riqaa Style This pen style evolved from both the Naskh and Thuluth designs around 886 AH. Its name is derived from the riqaa sheet or leather spread used to scribe on. Riq’a is a simple script with geometric rules similar to those of Thuluth but with smaller characters displaying more curves and short horizontal stems. This font is the most practiced for handwriting and ranks after Naskh. Most contemporary scholars and students used a combined version of both pens. This distinct style emerged in the Ottoman era and only later afterwards adopted and appropriated by Arab artists. Today, children are taught Naskh then introduced to Riqaa. A leading calligrapher in the Riqaa font was Mumtaz bek, an apprentice to the Ottoman Sultan Abdul- Majeed Khan (1280 AH). 5. The Diwani Style. This was the official script of state and administration as can be inferred from its name and was indeed the style used in official writing. It was named the “royal script” as it was used mainly in the imperial palace and museums, and used to write most royal decrees. The word “diwan” in Arabic means “government’s offices”. Records of correspondences were scribed in Diwani as it was the favorite for chancellery, in addition to many other manuscripts kept in the caliphate library. The Diwani writing is highly structured spangled with decorative marks and characterized by its adorned and decorated tails. This style flourished during the Ottoman Caliphate and was practiced over a period of nearly five hundred years and delivered to the following generations whom produced illuminated inscriptions and artwork. The Diwani script was founded by the well known calligrapher Shaykh Hamad-Allah Al-Amasa in 926 AH. 6. The Farisi Style This style was also known as Ta’liq or Nas-ta’liq which combined both the Naskh and Ta’liq geometric drawing rules in its application. The beautiful Farisi or Persian script is known with its brisk letters all drawn in one direction. While drawn with lenient and cursive characters, the style is easier to master and was a favorite in ornamental objects. The Farisi style came in use since the early 9th Hijri century (16th century CE) and flourished in the eastern Islamic regions of Persia and India. 7. The Moroccan Style This font is derived directly from the Koufi style and regulated with similar geometrical principles, uniformly it developed its distinct form. It was initially named the Qirawani font attributed to the Qirawan the capital of the Moroccan province but later known as the Morrocan style. Many copies of the Quran were scribed in this font in the northern provinces of Africa as well as Andalusia. This script is characterized with rounded large letters. To date, the Quran is scribed consistently in north African countries with this unique font.References

• Al-Kurdi, M. T. (1939) The History of Arabic Calligraphy and Arts, Egypt, The Hilal Book Publishers (Arabic book). • Al-Oufi, M. S. (2002) The Development of the Arabic Quranic Script, Al-Medina, KSA, The King Fahd Quran Complex (Arabic reference).

The Basmalah in traditional Koufi-

calligrapher Uthman Hamid, Kuwait

A prayer in Thuluth style

A prayer in Naskh style

Allah in simple Riqaa

A prayer in traditional Diwani Script